Section 7.1 Solving Quadratic Equations by Using a Square Root

In this section, we will learn how to solve some specific types of quadratic equations using the square root property. We will also learn how to use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of one side of a right triangle when the other two lengths are known.

Subsection 7.1.1 Solving Quadratic Equations Using the Square Root Property

When we learned how to solve linear equations, we used inverse operations to isolate the variable. For example, we use subtraction to remove an unwanted term that is added to one side of a linear equation. We can’t quite do the same thing with squaring and using square roots, but we can do something very similar. Taking the square root is the inverse of squaring if you happen to know the original number was positive. In general, we have to remember that the original number may have been negative, and that usually leads to two solutions to a quadratic equation.

For example, if \(x^2=9\text{,}\) we can think of undoing the square with a square root, and \(\sqrt{9}=3\text{.}\) However, there are two numbers that we can square to get \(9\text{:}\) \(-3\) and \(3\text{.}\) So we need to include both solutions. This brings us to the Square Root Property.

Fact 7.1.2. Square Root Property.

If \(k\) is positive, and \(x^2=k\) then

\begin{equation*}

x=-\sqrt{k}\qquad\text{ or }\qquad x=\sqrt{k}\text{.}

\end{equation*}

It is common to write \(x=\pm\sqrt{k}\) for short, but it is important to remember that this means \(x\) could possibly be one of two things, not that \(x\) is two things at the same time. The positive solution, \(\sqrt{k}\text{,}\) is called the principal root of \(k\text{.}\)

Example 7.1.3.

Solve for \(y\) in \(y^2=49\text{.}\)

Explanation.

\begin{align*}

y^2\amp=49\\

y\amp=\pm\sqrt{49}\\

y\amp=\pm7

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

y\amp=-7\amp\text{ or }\amp\amp y\amp=7

\end{align*}

To check these solutions, we will substitute \(-7\) and \(7\) for \(y\) in the original equation:

\begin{align*}

y^2\amp=49\amp y^2\amp=49\\

(\substitute{-7})^2\amp\wonder{=}49\amp (\substitute{7})^2\amp\wonder{=}49\\

49\amp\confirm{=}49\amp 49\amp\confirm{=}49

\end{align*}

The solution set is \(\{-7,7\}\text{.}\)

Remark 7.1.4.

Every solution to a quadratic equation can be checked, as shown in Example 3. In general, the process of checking is omitted from this section.

Checkpoint 7.1.5.

Solve for \(z\) in \(4z^2-81=0\text{.}\)

Explanation.

Before we use the square root property we need to isolate the squared quantity.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

4z^2-81\amp=0\\

4z^2\amp=81\\

z^2\amp=\frac{81}{4}\\

z\amp=\pm\sqrt{\frac{81}{4}}\\

z\amp=\pm\frac{9}{2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

z\amp=-\frac{9}{2}\amp\text{ or }\amp\amp z\amp=\frac{9}{2}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

The solution set is \(\left\{-\frac{9}{2},\frac{9}{2}\right\}\text{.}\)

We can also use the square root property to solve an equation that has a squared expression (as opposed to just having a squared variable).

Example 7.1.6.

Solve for \(p\) in \(50=2(p-1)^2\text{.}\)

Explanation.

It’s important here to suppress any urge you may have to expand the squared binomial. We begin by isolating the squared expression.

\begin{align*}

50\amp=2(p-1)^2\\

\divideunder{50}{2}\amp=\divideunder{2(p-1)^2}{2}\\

25\amp=(p-1)^2

\end{align*}

Now that we have the squared expression isolated, we can use the square root property.

\begin{align*}

p-1\amp=\pm\sqrt{25}\\

p-1\amp=\pm5\\

p\amp=\pm5+1

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

p\amp=-5+1\amp\text{or}\amp\amp p\amp=5+1\\

p\amp=-4\amp\text{or}\amp\amp p\amp=6

\end{align*}

The solution set is \(\{-4,6\}\text{.}\)

This method of solving quadratic equations is not limited to equations that have rational solutions, or when the radicands are perfect squares. Here are a few examples where the solutions are irrational numbers.

Checkpoint 7.1.7.

Solve for \(q\) in \((q+2)^2-12=0\text{.}\)

Explanation.

It’s important here to suppress any urge you may have to expand the squared binomial.

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

(q+2)^2-12\amp=0\\

(q+2)^2\amp=12\\

q+2\amp=\pm\sqrt{12}\\

q+2\amp=\pm\sqrt{4\cdot3}\\

q+2\amp=\pm2\sqrt{3}\\

q\amp=\pm2\sqrt{3}-2

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

q\amp=-2\sqrt{3}-2\amp\text{or}\amp\amp q\amp=2\sqrt{3}-2

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

The solution set is \(\left\{-2\sqrt{3}-2,2\sqrt{3}-2\right\}\text{.}\)

To check the solution, we would replace \(q\) with each of \(-2\sqrt{3}-2\) and \(2\sqrt{3}-2\) in the original equation, as shown here:

\begin{equation*}

\begin{aligned}

\left(\left(\substitute{-2\sqrt{3}-2}\right)+2\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\amp\amp\amp\left(\left(\substitute{2\sqrt{3}-2}\right)+2\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\\

\left(-2\sqrt{3}\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\amp\amp\amp \left(2\sqrt{3}\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\\

(-2)^2\left(\sqrt{3}\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\amp\amp\amp (2)^2\left(\sqrt{3}\right)^2-12\amp\wonder{=}0\\

(4)(3)-12\amp\wonder{=}0\amp\amp\amp (4)(3)-12\amp\wonder{=}0\\

12-12\amp\confirm{=}0\amp\amp\amp 12-12\amp\confirm{=}0

\end{aligned}

\end{equation*}

Note that these simplifications relied on exponent rules and the multiplicative property of square roots.

Remember that if a square root is in a denominator then we may be expected to rationalize it as in Section 6.2. We will rationalize the denominator in the next example.

Example 7.1.8.

Solve for \(n\) in \(2n^2-3=0\text{.}\)

Explanation.

\begin{align*}

2n^2-3\amp=0\\

2n^2\amp=3\\

n^2\amp=\frac{3}{2}\\

n\amp=\pm\sqrt{\frac{3}{2}}\\

n\amp=\pm\sqrt{\frac{6}{4}}\\

n\amp=\pm\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}

\end{align*}

\begin{align*}

n\amp=-\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}\amp\text{ or }\amp\amp n\amp=\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}

\end{align*}

The solution set is \(\left\{-\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2},\frac{\sqrt{6}}{2}\right\}\text{.}\)

When the radicand is a negative number, there is no real solution. Here is an example of an equation with no real solution.

Example 7.1.9.

Solve for \(x\) in \(x^2+49=0\text{.}\)

Explanation.

\begin{align*}

x^2+49\amp=0\\

x^2\amp=-49

\end{align*}

Since \(\sqrt{-49}\) is not a real number, we say the equation has no real solution.

Subsection 7.1.2 The Pythagorean Theorem

Right triangles have an important property called the Pythagorean Theorem.

Theorem 7.1.10. The Pythagorean Theorem.

For any right triangle, the lengths of the three sides have the following relationship: \(a^2+b^2=c^2\text{.}\) The sides \(a\) and \(b\) are called legs and the longest side \(c\) is called the hypotenuse.

Example 7.1.12.

Keisha is designing a wooden frame in the shape of a right triangle, as shown in Figure 13. The legs of the triangle are 3 ft and 4 ft. How long should she make the diagonal side? Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find the length of the hypotenuse.

According to Pythagorean Theorem, we have:

\begin{align*}

c^2\amp=a^2+b^2\\

c^2\amp=3^2+4^2\\

c^2\amp=9+16\\

c^2\amp=25\\

\end{align*}

Now we have a quadratic equation that we need to solve. We need to find the number that has a square of \(25\text{.}\) That is what the square root operation does.

\begin{align*}

c\amp=\sqrt{25}\\

c\amp=5

\end{align*}

The diagonal side Keisha will cut is 5 ft long.

Note that \(-5\) is also a solution of \(c^2=25\) because \((-5)^2=25\) but a length cannot be a negative number. We will need to include both solutions when they are relevant.

Example 7.1.14.

A \(16.5\)ft ladder is leaning against a wall. The distance from the base of the ladder to the wall is \(4.5\) feet. How high on the wall does the ladder reach?

The Pythagorean Theorem says:

\begin{align*}

a^2+b^2\amp=c^2\\

4.5^2+b^2\amp=16.5^2\\

20.25+b^2\amp=272.25\\

\end{align*}

Now we need to isolate \(b^2\) in order to solve for \(b\text{:}\)

\begin{align*}

20.25+b^2\subtractright{20.25}\amp=272.25\subtractright{20.25}\\

b^2\amp=252\\

\end{align*}

We use the square root property. Because this is a geometric situation we only need to use the principal root:

\begin{align*}

b\amp=\sqrt{252}\\

\end{align*}

Now simplify this radical and then approximate it:

\begin{align*}

b\amp=\sqrt{36\cdot 7}\\

b\amp=6\sqrt{7}\\

b\amp\approx 15.87

\end{align*}

The ladder reaches about \(15.87\) feet high on the wall.

Here are some more examples using the Pythagorean Theorem to find sides of triangles. Note that in many contexts, only the principal root will be relevant.

Example 7.1.16.

Find the missing length in this right triangle.

Explanation.

We will use the Pythagorean Theorem to solve for \(x\text{:}\)

\begin{align*}

5^2+x^2\amp=10^2\\

25+x^2\amp=100\\

x^2\amp=75\\

x\amp=\sqrt{75}\amp\text{(no need to consider }{-\sqrt{75}}\text{ in this context)}\\

x\amp=\sqrt{25\cdot3}\\

x\amp=5\sqrt{3}

\end{align*}

The missing length is \(x=5\sqrt{3}\text{.}\)

Example 7.1.18.

Sergio is designing a \(50\)-inch TV, which implies the diagonal of the TV’s screen will be \(50\) inches long. He needs the screen’s width to height ratio to be \(4:3\text{.}\) Find the TV screen’s width and height.

Explanation.

Let’s let \(x\) represent the height of the screen, in inches. Since the screen’s width to height ratio will be \(4:3\text{,}\) then the width is \(\frac{4}{3}\) times as long as the height, or \(\frac{4}{3}x\) inches. We will draw a diagram.

Now we can use the Pythagorean Theorem to write and solve an equation:

\begin{align*}

a^2+b^2\amp=c^2\\

\left(\frac{4}{3}x\right)^2+x^2\amp=50^2\\

\frac{16}{9}x^2+\frac{9}{9}x^2\amp=2500\\

\frac{25}{9}x^2\amp=2500\\

\multiplyleft{\frac{9}{25}}\frac{25}{9}x^2\amp=\multiplyleft{\frac{9}{25}}2500\\

x^2\amp=900\\

x\amp=30

\end{align*}

Since the screen’s height is \(30\) inches, its width is \(\frac{4}{3}x=\frac{4}{3}(30)=40\) inches.

Example 7.1.21.

Luca wanted to make a bench.

He wanted the top of the bench back to be a perfect portion of a circle, in the shape of an arc, as in Figure 23. (Note that this won’t be a half-circle, just a small portion of a circular edge.) He started with a rectangular board \(6\) inches wide and \(48\) inches long, and a piece of string, like a compass, to draw a circular arc on the board. How long should the string be so that it can be swung round to draw the arc?

Explanation.

Let’s first define \(x\) to be the radius of the circle in question, in inches. The circle should go through the bottom corners of the board and just barely touch the top of the board. That means that the line from the middle of the bottom of the board to the center of the circle will be \(6\) inches shorter than the radius.

Now we can set up the Pythagorean Theorem based on the scenario. The equation \(a^2+b^2=c^2\) turns into…

\begin{align*}

(x-6)^2+24^2\amp=x^2\\

x^2-12x+36+576\amp=x^2\\

-12x+612\amp=0\\

\end{align*}

Note that at this point the equation is no longer quadratic! Solve the linear equation by isolating \(x\)

\begin{align*}

-12x\amp=-612\\

x\amp=51

\end{align*}

So, the circle radius required is \(51\) inches. Luca found a friend to stand on the string end and drew a circular segment on the board to great effect.

Reading Questions 7.1.3 Reading Questions

1.

Typically, how many solutions can there be with a quadratic equation?

2.

When you see a \(\pm\) sign, as in \(x=\pm2\text{,}\) is that saying that \(x\) is both \(-2\) and \(2\text{?}\)

3.

Have you memorized the Pythagorean Theorem? State the formula.

Exercises 7.1.4 Exercises

Solving Quadratic Equations with the Square Root Property.

1.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 81\)

2.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 100\)

3.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = {{\frac{1}{121}}}\)

4.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = {{\frac{1}{144}}}\)

5.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 12\)

6.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 20\)

7.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 13\)

8.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = 19\)

9.

Solve the equation.

\(6x^2 = 54\)

10.

Solve the equation.

\(7x^2 = 28\)

11.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = {{\frac{81}{100}}}\)

12.

Solve the equation.

\(x^2 = {{\frac{49}{16}}}\)

13.

Solve the equation.

\(64x^2 = 9\)

14.

Solve the equation.

\(9x^2 = 100\)

15.

Solve the equation.

\(19x^2 - 7= 0\)

16.

Solve the equation.

\(2x^2 - 13= 0\)

17.

Solve the equation.

\(0-5y^2 = -3\)

18.

Solve the equation.

\(-4-3r^2 = -9\)

19.

Solve the equation.

\(67x^2 + 41= 0\)

20.

Solve the equation.

\(41x^2 + 47= 0\)

21.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(x+8\right)^2 = 25\)

22.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(x+10\right)^2 = 144\)

23.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(x - 9\right)^2 = 64\)

24.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(x - 6\right)^2 = 16\)

25.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(8x+4\right)^2 = 121\)

26.

Solve the equation.

\(\left(3x+6\right)^2 = 64\)

27.

Solve the equation.

\(14 - 3 ( r - 8 )^2 = 2\)

28.

Solve the equation.

\(50 - 6 ( r - 9 )^2 = -4\)

29.

Solve the equation.

\((x - 4)^2 = 47\)

30.

Solve the equation.

\((x - 7)^2 = 59\)

31.

Solve the equation.

\((t - 9)^2 = 98\)

32.

Solve the equation.

\((x - 6)^2 = 45\)

33.

Solve the equation.

\(-10 = 18 - (x+9)^2\)

34.

Solve the equation.

\(-10 = 137 - (y+3)^2\)

Pythagorean Theorem Applications.

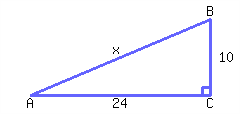

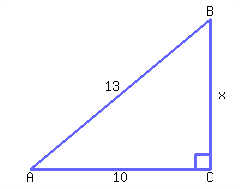

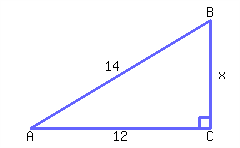

35.

Find the value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

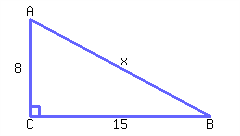

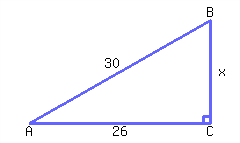

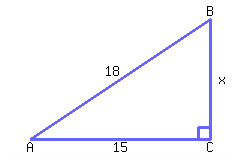

36.

Find the value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

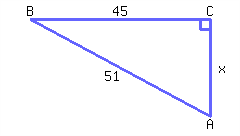

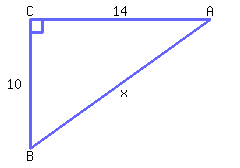

37.

Find the value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

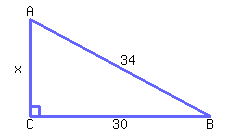

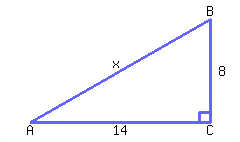

38.

Find the value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

39.

Find the value of \(x\text{,}\) accurate to at least two decimal places.

\(x\approx{}\)

40.

Find the value of \(x\text{,}\) accurate to at least two decimal places.

\(x\approx{}\)

41.

Find the exact value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

42.

Find the exact value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

43.

Find the exact value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

44.

Find the exact value of \(x\text{.}\)

\(x={}\)

Exercise Group.

45.

Teresa is designing a rectangular garden. The garden’s diagonal must be \(42.5\) feet, and the ratio between the garden’s base and height must be \(15:8\text{.}\) Find the length of the garden’s base and height.

The garden’s base is feet and its height is .

46.

Lisa is designing a rectangular garden. The garden’s diagonal must be \(18.2\) feet, and the ratio between the garden’s base and height must be \(12:5\text{.}\) Find the length of the garden’s base and height.

The garden’s base is feet and its height is .

47.

Donna is designing a rectangular garden. The garden’s base must be \(4.5\) feet, and the ratio between the garden’s hypotenuse and height must be \(17:8\text{.}\) Find the length of the garden’s hypotenuse and height.

The garden’s hypotenuse is feet and its height is .

48.

Subin is designing a rectangular garden. The garden’s base must be \(12.8\) feet, and the ratio between the garden’s hypotenuse and height must be \(5:3\text{.}\) Find the length of the garden’s hypotenuse and height.

The garden’s hypotenuse is feet and its height is .

Isolating a Variable.

49.

Solve the equation for \(R\text{.}\) Assume that \(R\) is positive.

\begin{equation*}

{Z} = {\sqrt{L^{2}+R^{2}}}

\end{equation*}

\(R =\) .

50.

According to the Pythagorean Theorem, the length \(c\) of the hypothenuse of a rectangular triangle can be found through the following equation:

\begin{equation*}

{c} = {\sqrt{a^{2}+b^{2}}}

\end{equation*}

Solve the equation for the length \(a\) of one of the triangle’s legs.

\(a =\) .

Challenge.

51.

Imagine that you are in Math Land, where roads are perfectly straight, and Mathlanders can walk along a perfectly straight line between any two points. One day, you bike 3 miles west, 7 miles north, and 7 miles east. Then, your bike gets a flat tire and you have to walk home. How far do you have to walk?

You have to walk miles home.

You have attempted of activities on this page.