Identify the sample/random process for this study.

Section 2.2 Investigation 1.2: Can Wolves Understand Human Cues?

Previous research has demonstrated that domesticated dogs can be trained to understand human cues, such as looking or pointing at an object. But it was not clear how the animals would perform with "behavioral cues" showing intent such as reaching for, but not obtaining, or trying to open an object.

Lampe et al. (2017) gave captive wolves, pack dogs living in identical conditions to the wolves, and pet dogs living with families a series of "object-choice tasks." A table was placed outside a fenced compartment, and a container was placed at each end of the table, one containing food and one empty. The experimenter would give the cue as to which container had the food and then the animal would touch one of the two targets next to the containers. A 6-year-old female timber wolf, Yukon, chose the intended container in 6 of the 8 trials with behavioral cues.

Checkpoint 2.2.1. Identify Sample and Process.

Checkpoint 2.2.2. Identify the Variable.

Identify the variable of interest for this process.

Checkpoint 2.2.3. Classify Variable Type.

Is this variable quantitative or categorical?

- Categorical

- Correct! The variable records which category (cued or not cued) Yukon chose, making it a categorical variable.

- Quantitative

- Not quite. A quantitative variable would be a numerical measurement. Here we’re recording which container was chosen, which is a category.

Checkpoint 2.2.4. Expected Success Rate.

If Yukon was purely guessing, how often would you expect her to identify the correct container?

- about 50% of the time

- Correct! With two equally likely options, we would expect Yukon to choose correctly about half the time by chance.

- about 33% of the time

- This would be the probability if there were three equally likely options.

- about 75% of the time

- This would mean Yukon has some understanding of the cues, not just guessing.

- about 25% of the time

- This would be the probability if there were four equally likely options.

- never

- Even when guessing, there’s a chance of being correct.

We will think of the sample of 8 attempts as identical observations from a random process, and we are choosing between two possibilities:

-

Yukon can understand behavioral cues,

-

Yukon does not consistently understand behavioral cues and is guessing randomly.

Definition: Hypotheses.

In drawing conclusions beyond our sample data to the underlying random process, we will often be choosing between two competing claims about the underlying process:

-

The null hypothesis, which is the "by chance alone" explanation;

-

The alternative hypothesis, which is usually what the researchers are hoping to show.

In Investigation 1.1, the null hypothesis was that infants (in general) choose equally among the two toys in the long run. The alternative hypothesis was that infants have a genuine preference for the helper toy.

Aside: How to use matching questions.

Checkpoint 2.2.5. State Hypotheses.

Checkpoint 2.2.6. Plan the Simulation.

So our simulation model is going to assume the null hypothesis is true and we will see how unusual it is to find 6 successes and 2 failures in 8 attempts. Can we use "coin tossing" again? How many times will we toss the coin?

Checkpoint 2.2.7.

Use the One Proportion Inference applet to carry out 1,000 repetitions of the simulation. Check the Summary Statistics box and report the mean and standard deviation of your simulated distribution of "could have been" outcomes.

Mean: Standard deviation:

Checkpoint 2.2.8. Evaluate Surprise Level.

Based on your simulation results, which assumes Yukon is guessing, should we be very surprised to see 6 correct guesses? Explain/support your reasoning.

Measuring "Rareness".

In Investigation 1.1, the observed result (14) was pretty far in the tail of the distribution and you probably agreed that we could consider it unusual. This result (6 out of 8) is not as inconsistent with the null hypothesis; so where do we "draw the line"? First, we need agree on a measure of "rareness." We could just calculate the theoretical probability of 6 heads in 8 tosses (0.1094), but keep in mind that if we have a larger sample size (e.g., 100 tosses), then any individual outcome (e.g., 62 heads) will have a small probability. So we want to judge how extreme our observation is relative to the other observations in the simulated distribution. One way to do this is to count how many outcomes are as or even more extreme (even further from the expected value) than the observed outcome. For example, if we tell you that only 1% of rattlesnakes are longer than 2.5 meters, then you know to be very surprised to see a 3-meter rattlesnake and you may even begin to think that what you are looking at is not a rattlesnake at all!

Checkpoint 2.2.9. Calculate P-value.

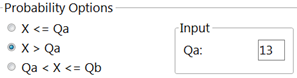

In the applet, enter 6 in the Count samples box and keep the "as extreme as" button to greater than or equal to, \(\geq\text{.}\) Report the proportion of the repetitions with 6 or more heads (correct choices).

In 1,000 repetitions, assuming the probability of choosing correctly is 0.50, we found % of repetitions of 8 attempts to result in 6 or more successes.

Notice that we consider the direction of the alternative hypothesis to help us determine which outcomes we consider "more extreme" than our observed outcome. This tail probability you found in (h) is referred to as the p-value.

Definition: Null Distribution and P-value.

Because the simulation assumes the null hypothesis to be true, we can refer to the distribution you simulated as the null distribution. When you determine the proportion of the results in the null distribution that are at least as extreme as the observed result, you are estimating a probability. We will refer to this probability as the p-value. We use the p-value to evaluate the strength of evidence against the null hypothesis.

The smaller the p-value, the stronger the evidence against the null hypothesis. There are no hard-and-fast cut-off values for gauging the smallness of a p-value, but generally speaking:

-

A p-value above 0.10 constitutes little or no evidence against the null hypothesis.

-

A p-value below 0.10 but above 0.05 constitutes moderate evidence against the null hypothesis.

-

A p-value below 0.05 but above 0.01 constitutes strong evidence against the null hypothesis.

-

A p-value below 0.01 constitutes very strong evidence against the null hypothesis.

Checkpoint 2.2.10. Compare P-values.

Did everyone in your class obtain the same p-value? (If not, are you surprised?)

- Yes

- Actually, because we’re using simulation, each person’s results will vary slightly.

- No

- Correct! The p-value will vary slightly across simulations because of the random nature of the process.

Because we are assuming a random process, we can use probability rules to calculate an "exact" value for the p-value. In fact, we have been assuming a very special random process, a binomial process.

Probability Detour – Binomial Random Variables.

Definition: Binomial Random Variable.

A Binomial random variable counts the number of successes in a random process with the following properties:

-

Each trial results in either "success" or "failure" (we have a binary categorical variable).

-

The trials are independent: The outcome of one trial does not change the probability of success on the next trial.

-

The probability of success, \(\pi\text{,}\) is constant across the trials.

-

There are a fixed number of trials, \(n\text{.}\)

If the number of successes, \(X\text{,}\) is a binomial random variable, then we can say \(X \sim \text{Binomial}(n, \pi)\text{.}\)

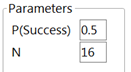

Because we are assuming the null hypothesis to be true, we are treating each attempt as an identical repetition of a random process with a probability of success of 0.50 for each attempt (always two containers to choose from), and one attempt outcome does not impact the probability of success on the next attempt (e.g., a screen was lowered between attempts and the location of the food randomized each time) so the attempts are independent. We are counting \(X\text{,}\) the observed number of correct choices in the \(n = 8\) trials. So \(X \sim\) (is distributed as) \(\text{Binomial}(8, 0.50)\) and we want to determine the probability of observing 6 or more successes in 8 attempts by chance alone, \(P(X \geq 6)\text{.}\) We will illustrate this calculation next, and then turn to technology to find binomial probabilities.

Calculating Binomial Probabilities.

Checkpoint 2.2.11. Calculate Single Outcome Probability.

Let S represent Success and F represent Failure. Consider one particular outcome for the 8 trials with 6 successes: SSFSSSFS. Because we are assuming the trials are independent, we can find the probability of this event by multiplying together the probabilities of the individual outcomes in the event.

\begin{align*}

P(\text{SSFSSSFS}) \amp = P(S) \times P(S) \times P(F) \times P(S)\\

\amp \quad \times P(S) \times P(S) \times P(F) \times P(S)

\end{align*}

What is the calculated product?

Checkpoint 2.2.12. Count Arrangements.

But there are other possible outcomes that would also result in 6 successes and 2 failures (for example, SFSSSSSF). How many ways are there to arrange the 6 successes among the 8 slots?

This is where the binomial coefficient comes in handy. This binomial coefficient, denoted by \(C(n, k)\) or \(\binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\text{,}\) counts the number of ways there are to select \(k\) items from a set of \(n\) items. In this case, we want to find the number of ways to select 6 spots from the 8 trials for the successes:

\begin{equation*}

C(8, 6) = \frac{8!}{6!2!}

\end{equation*}

What is the calculated result?

Checkpoint 2.2.13. Calculate Probability for 6 Successes.

Because the 28 outcomes corresponding to 6 successes are mutually exclusive (can’t occur simultaneously), we can find the probability of at least one of them happening by adding all of the probabilities together:

\begin{equation*}

P(\text{SSFSSSFS}) + P(\text{SFSSSSSF}) + \ldots = 28 \times (0.5^8)

\end{equation*}

What is the calculated product?

In general, the binomial probability of obtaining \(k\) successes in a sequence of \(n\) independent trials with success probability \(\pi\) on each trial is:

\begin{equation*}

P(X = k) = \binom{n}{k} \pi^k (1-\pi)^{n-k}

\end{equation*}

where \(\binom{n}{k} = \frac{n!}{k!(n-k)!}\)

Checkpoint 2.2.14. Calculate Complete P-value.

Is the number you found in (l) our p-value for this study? If not, how would we find the p-value?

Checkpoint 2.2.15.

In the One Proportion Inference applet, check the Exact Binomial box. (Optional: See Technology Detour below.) How does the binomial distribution match up to your earlier simulation results? How does the binomial (or "exact") p-value compare to what you simulated earlier? Did everyone in class obtain the same "exact" p-value?

Checkpoint 2.2.16. Interpret P-value.

Write a one-sentence interpretation of this p-value in this context. Key components to include: what random process is being repeated, what is the null hypothesis that we are assuming to be true, what is the observed result we are considering, which outcomes are we considering to be more extreme?

Conclusions.

Checkpoint 2.2.17. State Conclusion.

Based on this analysis, do these data provide convincing evidence that wolves can understand behavioral cues?

Study Conclusions.

If we assume Yukon is guessing between the two containers, regardless of the cue, then finding 6 or more successes in 8 trials is actually not very surprising (binomial p-value = 0.1445); about 14% of samples from a 50/50 process would show 6 or more successes in 8 trials. This does not provide convincing evidence that Yukon can perform "above chance," but there is not information about whether other wolves or other cues would show better performance.

Subsection 2.2.1 Practice Problem 1.2A

When Yukon was given "communicative cues" (looking at the container, pointing to the container) instead of behavioral cues, she was correct in 7 out of 8 attempts. Does this outcome provide convincing evidence that wolves understand communicative cues?

Checkpoint 2.2.19. Calculate and Interpret P-value.

Checkpoint 2.2.20. Summarize Analysis and Conclusions.

Summarize your analysis and the conclusions you would draw from this study.

Checkpoint 2.2.21. Evaluate Pooled Data Analysis.

Across the 12 wolves in the study, in the 64 trials with communicative cues, the wolves understood the cue 41 times. What is the new p-value for these results? Explain why this would not be an appropriate analysis.

Subsection 2.2.2 Practice Problem 1.2B

A study in Psychonomic Bulletin and Review (Lea, Thomas, Lamkin, & Bell, 2007) presented evidence that "people use facial prototypes when they encounter different names." Similar to one of the experiments they conducted, you will be asked to match photos of two faces to the names Tim and Bob. The researchers wrote that their participants "overwhelmingly agreed" on which face belonged to Tim. You will conduct a similar study in class to see whether your class also agrees with which face is Tim’s more than you would expect from random chance (here "random chance" = there is no facial prototyping and people pick a name for the face on the left at random).

Checkpoint 2.2.22. Identify Process and Variable.

What is the sample/random process and variable in this study? What assumptions are we making about this process?

Checkpoint 2.2.24. Report Class Results.

Report the count, proportion, and percentage "correctly" identifying Tim’s face in your class.

Checkpoint 2.2.25. Calculate P-value and Conclude.

Use the applet or the technology instructions below to obtain a binomial p-value. What do you conclude about the null hypothesis?

Checkpoint 2.2.26. Verify Binomial Assumptions.

Do you think the properties of the binomial random variable are met here? What assumptions need to be made?

Technology Detour – Calculating Binomial Probabilities.

Checkpoint 2.2.27. Calculating Binomial Probabilities in R.

Make sure you have the ISCAM Workspace loaded.

The

iscambinomprob function takes the following inputs:

-

k= the observed value you want to calculate the probability about -

n= the sample size of the binomial distribution -

prob= the probability of success in the binomial distribution -

lower.tail= TRUE if you want the probability less than or equal to the observed value, FALSE if want the probability greater than or equal to the observed value

For the Friend or Foe study, in the Console at the prompt, type:

iscambinomprob(k=14, n=16, prob=.5, lower.tail=FALSE)

or

iscambinomprob(14, 16, .5, FALSE)

(Yes, "false" needs to be capitalized)

You should see both the probability appear in the Console window and a shaded graph open in a separate Graphics window. (You may have to toggle windows to see this Graphics window.)

Note 2.2.28. R Reminder.

The

iscambinomprob function is part of the ISCAM package. Make sure to load the package first with library(iscam). The lower.tail parameter controls the direction: FALSE gives you \(P(X \geq k)\text{,}\) TRUE gives you \(P(X \leq k)\text{.}\)

Checkpoint 2.2.29. Calculating Binomial Probabilities in JMP.

Using the Distribution Calculator in the ISCAM Journal File (Download this file to your computer and then open the .jrn file to launch JMP.)

Solution.

You have attempted of activities on this page.