Principle 11.5.1. DEBUGGING TIP: End of Binary File.

Because a binary file does not have an end-of-file character, it would be an error to use the same loop-entry conditions we used in the loops we designed for reading text files.

String, ints, double —it cannot be processed as text. Similarly, a company’s inventory files, which also include data of a wide variety of types, cannot be processed as text. Files such as these must be processed as binary data.

Connect a stream to the file.

Read or write the data, possibly using a loop.

Close the stream.

Name0 24 15.06

Name1 25 5.09

Name2 40 11.45

Name3 52 9.25

String, int, double—and have the right kind of values. Of course, when these data are stored in the file, or in the program’s memory, they just look like one long string of 0’s and 1’s.

java.io package Figure 11.2.4 and Table 11.2.7).

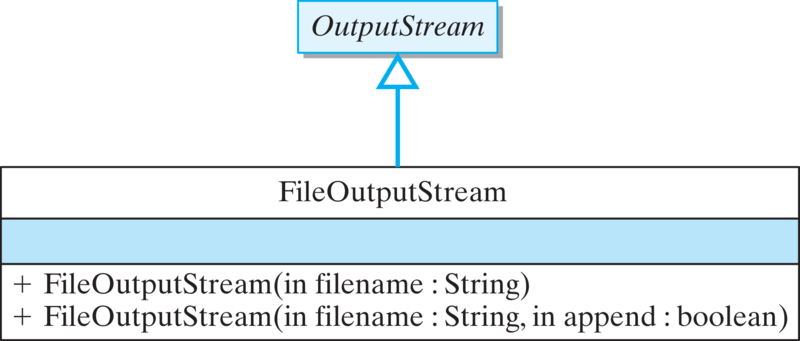

FileOutputStream class.OutputStream. Because we’re outputting to a file, one likely candidate is FileOutputStream(Fig. Figure 11.5.4). This class has the right kind of constructors, but it only contains write() methods for writing int and byte data, and we need to be able to write String and double data as well.

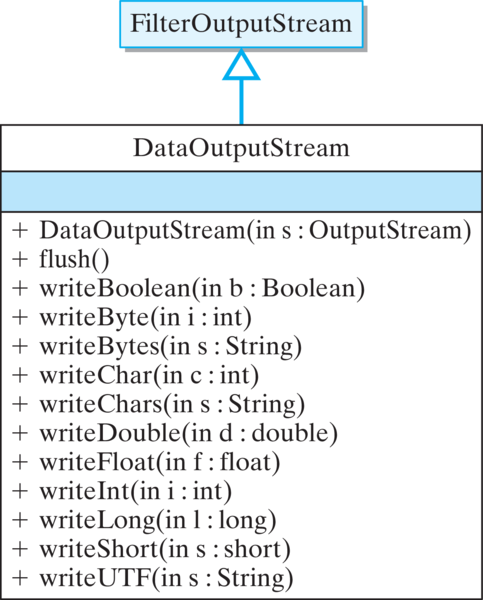

DataOutputStream (Figure 11.5.5), which contains a write() method for each different type of data. As you can see, there’s one method for each primitive type. However, note that the writeChar() takes an int parameter, which indicates that the character is written in binary format rather than as a ASCII or Unicode character. Although you can’t tell by just reading its method signature, the writeChars(String) method also writes its data in binary format rather than as a sequence of characters. This is the main difference between these write() methods and the ones defined in the Writer branch of Java’s I/O hierarchy.

DataOutputStream class.DataOutputStream and a FileOutputStream. The DataOutputStream gives us the output methods we need, and the FileOutputStream lets us use the file’s name to create the stream:

DataOutputStream outStream

= new DataOutputStream(new FileOutputStream (fileName));

DataOutputStream, which will pass them through the FileOutputStream to the file itself. That settles the first question.

write() statement for each of the elements in the employee record: The name (String), age (int), and pay rate (double):

for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { // Output 5 data records

outStream.writeUTF("Name" + k); // Name

outStream.writeInt((int)(20 + Math.random() * 25)); //Age

outStream.writeDouble(Math.random() * 500); // Payrate}

writeInt() to write an int and writeDouble() to write a double. But why do we use writeUTF to write the employee’s name, a String?

DataOutputStream.writeString() method. Instead, Strings are written using the writeUTF() method. UTF stands for Unicode Text Format, a coding scheme for Java’s Unicode character set. Recall that Java uses the Unicode character set instead of the ASCII set. As a 16-bit code, Unicode can represent 8-bit ASCII characters plus a wide variety of Asian and other international characters.

writeRecords() method takes a single String parameter that specifies the name of the file. This is a void method. It will output data to a file, but it will not return anything to the calling method. The method follows the standard output algorithm: Create an output stream, write the data, close the stream. Note also that the method includes a try/catch block to handle any IOExceptions that might be thrown.

private void writeRecords( String fileName ) {

try {

DataOutputStream outStream // Open stream

= new DataOutputStream(new FileOutputStream(fileName));

for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { // Output 5 data records

String name = "Name" + k; // of name, age, payrate

outStream.writeUTF("Name" + k);

outStream.writeInt((int)(20 + Math.random() * 25));

outStream.writeDouble(5.00 + Math.random() * 10);

} // for

outStream.close(); // Close the stream

} catch (IOException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: " + e.getMessage() + "\n");

}

} // writeRecords()

writeRecords() method. We’ll call this method readRecords(). It, too, will consist of a single String parameter that provides the name of the file to be read, and it will be a void method. It will just display the data on System.out.

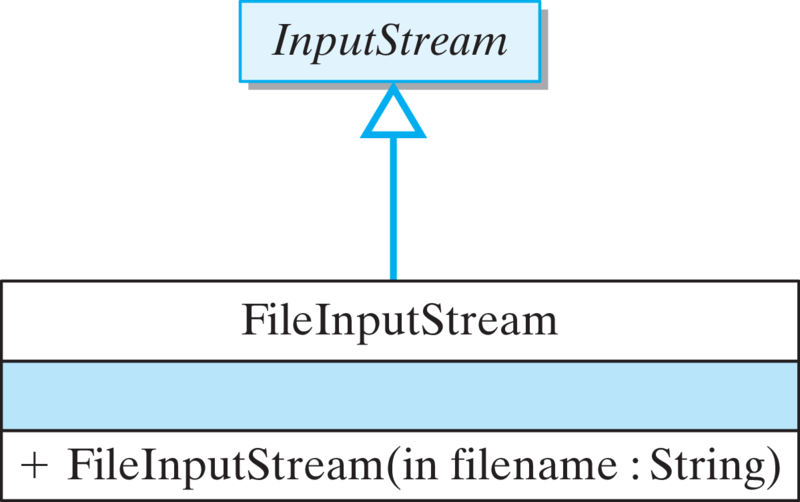

FileInputStream class.InputStream subclass (Figure 11.2.4 and Table 11.2.7). As you’ve probably come to expect, the FileInputStream class contains constructors that let us create a stream from a file name (Table 11.2.7). However, it does not contain useful read() methods.

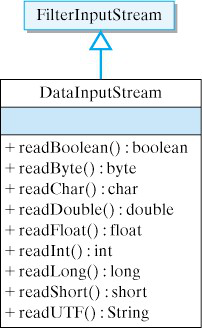

DataInputStream class contains methods for reading all types of data.DataInputStream class contains the input counterparts of the methods we found in DataOutputStream (Figure 11.5.8). Therefore, our input stream for this method will be a combination of DataInputStream and FileInputStream:

DataInputStream inStream

= new DataInputStream(new FileInputStream(file));

EOFException is thrown. Thus, the binary loop is coded as an infinite loop that’s exited when the EOFException is raised:

try {

while (true) { // Infinite loop

String name = inStream.readUTF(); // Read a record

int age = inStream.readInt();

double pay = inStream.readDouble();

display.append(name + " " + age + " " + pay + "\n");

} // while

} catch (EOFException e) {} // Until EOF exception

try/catch statement. Note that the catch clause for the EOFException does nothing. Recall that when an exception is thrown in a try block, the block is exited for good, which is precisely the action we want to take. That’s why we needn’t do anything when we catch the EOFException. We have to catch the exception or else Java will catch it and terminate the program. This is an example of an expected exception.

EOFException.

EOFException to be thrown. Catching this exception is the standard way of terminating a binary input loop.

read() statements within the loop are mirror opposites of the write() statements in the method that created the data. This will generally be true for binary I/O routines: The statements that read data from a file should “match” those that wrote the data in the first place.

writeX() method were used to write the data, a readX() should be used to read it.

close() the stream after the data are read. The complete definition is shown in Listing 11.5.11.

private void readRecords( String fileName ) {

try {

DataInputStream inStream // Open stream

= new DataInputStream(new FileInputStream(fileName));

display.setText("Name Age Pay\n");

try {

while (true) { // Infinite loop

String name = inStream.readUTF(); // Read a record

int age = inStream.readInt();

double pay = inStream.readDouble();

display.append(name + " " + age + " " + pay + "\n");

} // while

} catch (EOFException e) { // Until EOF exception

} finally {

inStream.close(); // Close the stream

}

} catch (FileNotFoundException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: "+ fileName + " NOT Found: \n");

} catch (IOException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: " + e.getMessage() + "\n");

}

} // readRecords()

close() statement be placed after the catch EOFException clause. If it were placed in the try block, it would never get executed. Note also that the entire method is embedded in an outer try block that catches the IOException, thrown by the various read() methods, and the FileNotFoundException, thrown by the FileInputStream() constructor. These make the method a bit longer, but conceptually they belong in this method.

finallyBlock.

EOFException is raised. Therefore, the close() statement must be placed in the finally clause, which is executed after the catch clause.

IOException s. The inner block encapsulates the read loop and catches the EOFException. No particular action need be taken when the EOFException is caught.

int?

public void readIntegers(DataInputStream inStream) {

try {

while (true) {

int num = inStream.readInt();

System.out.println(num);

}

inStream.close();

} catch (EOFException e) {

} catch (IOException e) {

}

} // readIntegers

inStream.close() statement is in the wrong place.public void readIntegers(DataInputStream inStream) {

try {

while (true) {

int num = inStream.readInt();

System.out.println(num);

}

} catch (EOFException e) {

} catch (IOException e) {

inStream.close();

}

} // readIntegers

inStream.close() statement is in the wrong place.public void readIntegers(DataInputStream inStream) {

try {

while (true) {

int num = inStream.readInt();

System.out.println(num);

}

} catch (EOFException e) {

} catch (IOException e) {

} finally {

inStream.close();

}

} // readIntegers

inStream.close() statement goes in the finally block.BinaryIO Application

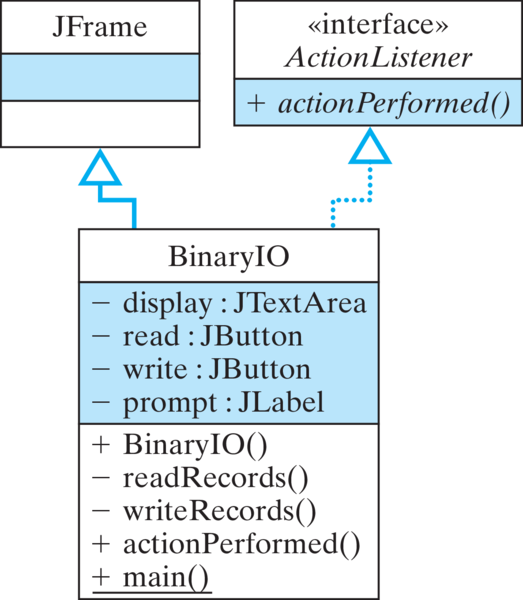

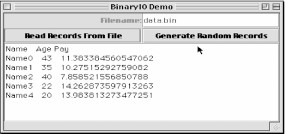

BinaryIO class (Figure 11.5.14). The program sets up the same interface we used in the text file example (Figure 11.5.15). It allows the user to specify the name of a data file to read or write. One button allows the user to write random employee records to a binary file, and the other allows the user to display the contents of a file in a JTextArea. The BinaryIO program in Figure 11.5.16 incorporates both readRecords() and writeRecords() into a complete Java program.

BinaryIO class illustrates simple input and output from a binary file.import javax.swing.*; // Swing components

import java.awt.*;

import java.io.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

public class BinaryIO extends JFrame implements ActionListener{

private JTextArea display = new JTextArea();

private JButton read = new JButton("Read Records From File"),

write = new JButton("Generate Random Records");

private JTextField nameField = new JTextField(10);

private JLabel prompt = new JLabel("Filename:", JLabel.RIGHT);

private JPanel commands = new JPanel();

public BinaryIO() {

super("BinaryIO Demo"); // Set window title

read.addActionListener(this);

write.addActionListener(this);

commands.setLayout(new GridLayout(2,2,1,1)); // Control panel

commands.add(prompt);

commands.add(nameField);

commands.add(read);

commands.add(write);

display.setLineWrap(true);

this.getContentPane().setLayout(new BorderLayout () );

this.getContentPane().add("North", commands);

this.getContentPane().add( new JScrollPane(display));

this.getContentPane().add("Center", display);

} // BinaryIO()

private void readRecords( String fileName ) {

try {

DataInputStream inStream // Open stream

= new DataInputStream(new FileInputStream(fileName));

display.setText("Name Age Pay\n");

try {

while (true) { // Infinite loop

String name = inStream.readUTF(); // Read a record

int age = inStream.readInt();

double pay = inStream.readDouble();

display.append(name + " " + age + " " + pay + "\n");

} // while

} catch (EOFException e) { // Until EOF exception

} finally {

inStream.close(); // Close the stream

}

} catch (FileNotFoundException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: File NOT Found: " + fileName + "\n");

} catch (IOException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: " + e.getMessage() + "\n");

}

} // readRecords()

private void writeRecords( String fileName ) {

try {

DataOutputStream outStream // Open stream

= new DataOutputStream(new FileOutputStream(fileName));

for (int k = 0; k < 5; k++) { // Output 5 data records

String name = "Name" + k; // of name, age, payrate

outStream.writeUTF("Name" + k);

outStream.writeInt((int)(20 + Math.random() * 25));

outStream.writeDouble(5.00 + Math.random() * 10);

} // for

outStream.close(); // Close the stream

} catch (IOException e) {

display.setText("IOERROR: " + e.getMessage() + "\n");

}

} // writeRecords()

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt) {

String fileName = nameField.getText();

if (evt.getSource() == read)

readRecords(fileName);

else

writeRecords(fileName);

} // actionPerformed()

public static void main(String args[]) {

BinaryIO bio = new BinaryIO();

bio.setSize(400, 200);

bio.setVisible(true);

bio.addWindowListener(new WindowAdapter() { // Quit

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent e) {

System.exit(0);

}

});

} // main()

} // BinaryIO

String followed by an int followed by a double, then they must be written by a sequence consisting of

writeUTF();

writeInt():

writeDouble();

readUTF();

readInt():

readDouble();

010100110011001001010100110011000

010100110011001011010100110011000

ints or two 32-bit floats or one 64-bit double or four 16-bit chars or a single String of 8 ASCII characters. We can’t tell what data we have unless we know exactly how the data were written.

int s or one long or even as some kind of object, so an int, long or an object is an abstraction imposed upon the data by the program.