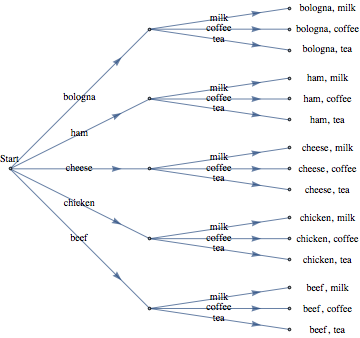

A snack bar serves five different sandwiches and three different beverages. How many different lunches can a person order? One way of determining the number of possible lunches is by listing or enumerating all the possibilities. One systematic way of doing this is by means of a tree, as in the following figure.

Tree diagram to enumerate the number of possible lunches. Starting at a node labeled Start, there are five branches, one for each possible sandwich that can be ordered. For each sandwich node there are three branches emanating from it, one for each possible beverage. The result is fifteen end nodes, one for each possible lunch.

Every path that begins at the position labeled START and goes to the right can be interpreted as a choice of one of the five sandwiches followed by a choice of one of the three beverages. Note that considerable work is required to arrive at the number fifteen this way; but we also get more than just a number. The result is a complete list of all possible lunches. If we need to answer a question that starts with “How many . . . ,” enumeration would be done only as a last resort. In a later chapter we will examine more enumeration techniques.

An alternative method of solution for this example is to make the simple observation that there are five different choices for sandwiches and three different choices for beverages, so there are \(5 \cdot 3 = 15\) different lunches that can be ordered.