For

\(n \geq 0\text{,}\) let

\(S(n)\) be the proposition: For all

\(g(x)\neq 0\) and

\(f(x)\) with

\(\deg f(x) = n\text{,}\) there exist unique polynomials

\(q(x)\) and

\(r(x)\) such that

\(f(x)=g(x)q(x)+r(x)\text{,}\) and either

\(r(x)=0\) or

\(\deg r(x) < \deg g(x)\text{.}\)

Basis:

\(S(0)\) is true, for if

\(f(x)\) has degree 0, it is a nonzero constant,

\(f(x)=c\neq 0,\) and so either

\(f(x) =g(x)\cdot 0 + c\) if

\(g(x)\) is not a constant, or

\(f(x) = g(x)g(x)^{-1}+0\) if

\(g(x)\) is also a constant.

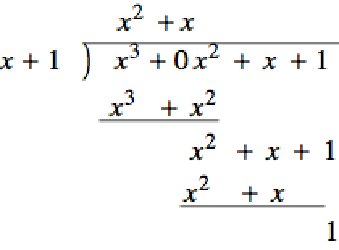

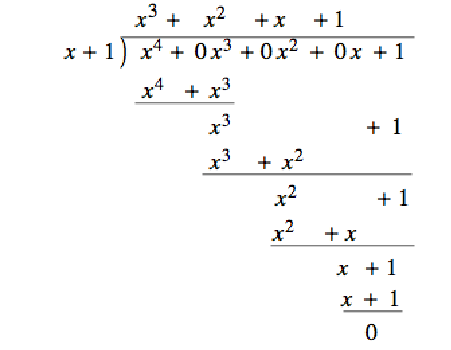

Induction: Assume that for some \(n\geq 0\text{,}\) \(S(k)\) is true for all \(k \leq n\text{,}\) If \(f(x)\) has degree \(n+1\text{,}\) then there are two cases to consider. If \(\deg g(x) > n + 1\text{,}\) \(f(x) = g(x)\cdot 0 + f(x)\text{,}\) and we are done. Otherwise, if \(\deg g(x) =m \leq n + 1\text{,}\) we perform long division as follows, where LDT’s stand for terms of lower degree than \(n+1\text{.}\)

\begin{equation*}

\begin{array}{rll}

& f_{n+1}\cdot g_m{}^{-1}x^{n+1-m} \\

g_mx^m+ \textrm{ LDT}'s & \overline{\left) f_{n+1}x^{n+1}\right.+ \textrm{ LDT}'s

\textrm{ }}& \\ & \underline{\textrm{ }f_{n+1}x^{n+1}+ \textrm{ LDT}'s}\textrm{

}\\& \quad\quad\quad\quad\quad h(x) \\

\end{array}

\end{equation*}

Therefore,

\begin{equation*}

h(x) = f(x)-\left(f_{n+1}\cdot g_m{}^{-1}x^{n+1-m}\right) g(x) \Rightarrow \textrm{ }f(x) = \left(f_{n+1}\cdot g_m{}^{-1}x^{n+1-m}\right)

g(x)+h(x)

\end{equation*}

Since \(\deg h(x)\) is less than \(n+1\text{,}\) we can apply the induction hypothesis: \(h(x) = g(x)q(x) + r(x)\) with \(\deg r(x) < \deg g(x)\text{.}\)

Therefore,

\begin{equation*}

f(x) = g(x)\left(f_{n+1}\cdot g_m{}^{-1}x^{n+1-m}+ q(x)\right) + r(x)

\end{equation*}

with \(\deg r(x) < \deg g(x)\text{.}\) This establishes the existence of a quotient and remainder. The uniqueness of \(q(x)\) and \(r(x)\) as stated in the theorem is proven as follows: if \(f(x)\) is also equal to \(g(x)\bar{q}(x) + \bar{r}(x)\) with deg \(\bar{r}(x) < \deg g(x)\text{,}\) then

\begin{equation*}

g(x)q(x) + r(x) = g(x) \bar{q}(x) +\overline{ r}(x) \Rightarrow g(x) \left(\bar{q}(x)-q(x)\right)= r(x)-\bar{r}(x)

\end{equation*}

Since \(\deg r(x) - \bar{r}(x) < \deg g(x)\text{,}\) the degree of both sides of the last equation is less than \(\deg g(x)\text{.}\) Therefore, it must be that \(\bar{q}(x) - q(x) = 0\text{,}\) or \(q(x) =\bar{q}(x)\) And so \(r(x) = \bar{r}(x)\text{.}\)