8.6. Tree Traversals¶

Now that we have examined the basic functionality of our tree data structure, it is time to look at some additional usage patterns for trees. These usage patterns can be divided into the three ways that we access the nodes of the tree. There are three commonly used patterns to visit all the nodes in a tree. The difference between these patterns is the order in which each node is visited. We call this visitation of the nodes a “traversal.” The three traversals we will look at are called preorder, inorder, and postorder. Let’s start out by defining these three traversals more carefully, then look at some examples where these patterns are useful.

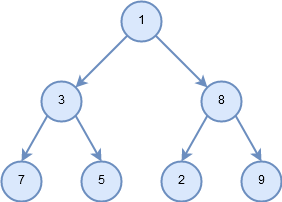

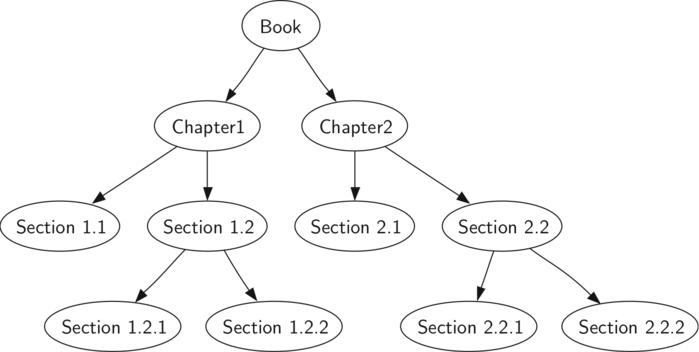

Figure 5: Example tree to be traversed.¶

- preorder

In a preorder traversal, we visit the root node first, then recursively do a preorder traversal of the left subtree, followed by a recursive preorder traversal of the right subtree.

Figure 6: Traversal pattern for preorder.¶

- inorder

In an inorder traversal, we recursively do an inorder traversal on the left subtree, visit the root node, and finally do a recursive inorder traversal of the right subtree.

Figure 7: Traversal pattern for inorder.¶

- postorder

In a postorder traversal, we recursively do a postorder traversal of the left subtree and the right subtree followed by a visit to the root node.

Figure 8: Traversal pattern for postorder.¶

Let’s look at some examples that illustrate each of these three kinds of traversals. First let’s look at the preorder traversal. As an example of a tree to traverse, we will represent this book as a tree. The book is the root of the tree, and each chapter is a child of the root. Each section within a chapter is a child of the chapter, and each subsection is a child of its section, and so on. Figure 5 shows a limited version of a book with only two chapters. Note that the traversal algorithm works for trees with any number of children, but we will stick with binary trees for now.

Figure 9: Representing a Book as a Tree¶

Suppose that you wanted to read this book from front to back. The

preorder traversal gives you exactly that ordering. Starting at the root

of the tree (the Book node) we will follow the preorder traversal

instructions. We recursively call preorder on the left child, in

this case Chapter1. We again recursively call preorder on the left

child to get to Section 1.1. Since Section 1.1 has no children, we do

not make any additional recursive calls. When we are finished with

Section 1.1, we move up the tree to Chapter 1. At this point we still

need to visit the right subtree of Chapter 1, which is Section 1.2. As

before we visit the left subtree, which brings us to Section 1.2.1, then

we visit the node for Section 1.2.2. With Section 1.2 finished, we

return to Chapter 1. Then we return to the Book node and follow the same

procedure for Chapter 2.

The code for writing tree traversals is surprisingly elegant, largely because the traversals are written recursively. Listing 2 shows the C++ code for a preorder traversal of a binary tree.

You may wonder, what is the best way to write an algorithm like preorder

traversal? Should it be a function that simply uses a tree as a data

structure, or should it be a method of the tree data structure itself?

Listing 2 shows a version of the preorder traversal

written as an external function that takes a binary tree as a parameter.

The external function is particularly elegant because our base case is

simply to check if the tree exists. If the tree parameter is None,

then the function returns without taking any action.

Listing 2

C++ Implementation

void preorder(BinaryTree *tree){

if (tree){

cout << tree->getRootVal() << endl;

preorder(tree->getLeftChild());

preorder(tree->getRightChild());

}

}

Python Implementation

def preorder(tree):

if tree:

print(tree.getRootVal())

preorder(tree.getLeftChild())

preorder(tree.getRightChild())

We can also implement preorder as a method of the BinaryTree

class. The code for implementing preorder as an internal method is

shown in Listing 3. Notice what happens when we move the

code from external to internal. In general, we just replace tree

with self. However, we also need to modify the base case. The

internal method must check for the existence of the left and the right

children before making the recursive call to preorder.

Listing 3

C++ Implementation

void preorder(){

cout << this->key << endl;

if (this->leftChild){

this->leftChild->preorder();

}

if (this->rightChild){

this->rightChild->preorder();

}

}

Python Implementation

def preorder(self):

print(self.key)

if self.leftChild:

self.leftChild.preorder()

if self.rightChild:

self.rightChild.preorder()

Which of these two ways to implement preorder is best? The answer is

that implementing preorder as an external function is probably

better in this case. The reason is that you very rarely want to just

traverse the tree. In most cases you are going to want to accomplish

something else while using one of the basic traversal patterns. In fact,

we will see in the next example that the postorder traversal pattern

follows very closely with the code we wrote earlier to evaluate a parse

tree. Therefore we will write the rest of the traversals as external

functions.

The algorithm for the postorder traversal, shown in

Listing 4, is nearly identical to preorder except that

we move the call to print to the end of the function.

Listing 4

C++ Implementation

void postorder(BinaryTree *tree){

if (tree != NULL){

postorder(tree->getLeftChild());

postorder(tree->getRightChild());

cout << tree->getRootVal() << endl;

}

}

Python Implementation

def postorder(tree):

if tree != None:

postorder(tree.getLeftChild())

postorder(tree.getRightChild())

print(tree.getRootVal())

We have already seen a common use for the postorder traversal, namely

evaluating a parse tree. Look back at Listing 1 again. What

we are doing is evaluating the left subtree, evaluating the right

subtree, and combining them in the root through the function call to an

operator. Assume that our binary tree is going to store only expression

tree data. Let’s rewrite the evaluation function, but model it even more

closely on the postorder code in Listing 4 (see Listing 5).

Listing 5

class Operator {

public:

int add(int x, int y){

return x + y;

}

int sub(int x, int y){

return x - y;

}

int mul(int x, int y){

return x * y;

}

int div(int x, int y){

return x / y;

}

};

int to_int(string str) {

stringstream convert(str);

int x = 0;

convert >> x;

return x;

}

string to_string(int num) {

string str;

ostringstream convert;

convert << num;

str = convert.str();

return str;

}

string evaluate(BinaryTree *parseTree) {

Operator Oper;

BinaryTree *leftC = parseTree->getLeftChild();

BinaryTree *rightC = parseTree->getRightChild();

if (leftC && rightC) {

if (parseTree->getRootVal() == "+") {

return to_string(Oper.add(to_int(evaluate(leftC)), to_int(evaluate(rightC))));

} else if (parseTree->getRootVal() == "-") {

return to_string(Oper.sub(to_int(evaluate(leftC)), to_int(evaluate(rightC))));

} else if (parseTree->getRootVal() == "*") {

return to_string(Oper.mul(to_int(evaluate(leftC)), to_int(evaluate(rightC))));

} else {

return to_string(Oper.div(to_int(evaluate(leftC)), to_int(evaluate(rightC))));

}

} else {

return parseTree->getRootVal();

}

}

int main(){

return 0;

}

class Operator {

public:

int add(int x, int y){

return x + y;

}

int sub(int x, int y){

return x - y;

}

int mul(int x, int y){

return x * y;

}

int div(int x, int y){

return x / y;

}

};

int to_int(string str) {

stringstream convert(str);

int x = 0;

convert >> x;

return x;

}

string t_string(int num) {

string str;

ostringstream convert;

convert << num;

str = convert.str();

return str;

}

string postordereval(BinaryTree *tree){

Operator Oper;

BinaryTree *res1 = tree->getLeftChild();

BinaryTree *res2 = tree->getRightChild();

if (tree) {

if (res1 && res2) {

if (tree->getRootVal() == "+") {

return t_string(Oper.add(to_int(postordereval(res1)), to_int(postordereval(res2))));

} else if (tree->getRootVal() == "-") {

return t_string(Oper.sub(to_int(postordereval(res1)), to_int(postordereval(res2))));

} else if (tree->getRootVal() == "*") {

return t_string(Oper.mul(to_int(postordereval(res1)), to_int(postordereval(res2))));

} else {

return t_string(Oper.div(to_int(postordereval(res1)), to_int(postordereval(res2))));

}

} else {

return tree->getRootVal();

}

}

}

def postordereval(tree):

opers = {'+':operator.add, '-':operator.sub, '*':operator.mul, '/':operator.truediv}

res1 = None

res2 = None

if tree:

res1 = postordereval(tree.getLeftChild())

res2 = postordereval(tree.getRightChild())

if res1 and res2:

return opers[tree.getRootVal()](res1,res2)

else:

return tree.getRootVal()

Notice that the form in Listing 4 is the same as the form in Listing 5, except that instead of printing the key at the end of the function, we return it. This allows us to save the values returned from the recursive calls in lines 6 and 7. We then use these saved values along with the operator on line 9.

The final traversal we will look at in this section is the inorder

traversal. In the inorder traversal we visit the left subtree, followed

by the root, and finally the right subtree. Listing 6 shows

our code for the inorder traversal. Notice that in all three of the

traversal functions we are simply changing the position of the print

statement with respect to the two recursive function calls.

Listing 6

C++ Implementation

void inorder(BinaryTree *tree){

if (tree != NULL){

inorder(tree->getLeftChild());

cout << tree->getRootVal();

inorder(tree->getRightChild());

}

}

Python Implementation

def inorder(tree):

if tree != None:

inorder(tree.getLeftChild())

print(tree.getRootVal())

inorder(tree.getRightChild())

If we perform a simple inorder traversal of a parse tree we get our original expression back, without any parentheses. Let’s modify the basic inorder algorithm to allow us to recover the fully parenthesized version of the expression. The only modifications we will make to the basic template are as follows: print a left parenthesis before the recursive call to the left subtree, and print a right parenthesis after the recursive call to the right subtree. The modified code is shown in Listing 7.

Listing 7

C++ Implementation

string printexp(BinaryTree *tree){

string sVal;

if (tree){

sVal = "(" + printexp(tree->getLeftChild());

sVal = sVal + tree->getRootVal();

sVal = sVal + printexp(tree->getRightChild()) + ")";

}

return sVal;

}

Python Implementation

def printexp(tree):

sVal = ""

if tree:

sVal = '(' + printexp(tree.getLeftChild())

sVal = sVal + str(tree.getRootVal())

sVal = sVal + printexp(tree.getRightChild())+')'

return sVal

Notice that the printexp function as we have implemented it puts

parentheses around each number. While not incorrect, the parentheses are

clearly not needed. In the exercises at the end of this chapter you are

asked to modify the printexp function to remove this set of parentheses.

-

Q-1: Drag the tree traversal to its corresponding pattern.

Review the tree traversal patterns.

- preorder

- root, left, right

- inorder

- left, root, right

- postorder

- left, right, root

- Book, Chapter 1, Section 1.1, Section 1.2, Section 1.2.2, Section 1.2.2, Chapter 2, Section 2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2

- correct

- Section 1.1, Chapter 1.2, Section 1.2.1, Section 1.2, Section 1.2.2, Section 2.1, Chapter 2, Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2, Section 2.2.2

- Incorrect, this is postorder traversal

- Section 1.1, Section 1.2.1, Section 1.2.2, Section 1.2, Chapter 1, Section 2.1, Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2, Section 2.2, Chapter 2, Book

- Incorrect, this is inorder traversal

Q-2: If you print out the data at each node, what would be the result of using the preorder traversal method on Figure 5?