6.1. File Handling¶

File handling in C++ also uses a stream in a similar way to the cout and cin functions of <iostream>. The library that allows for input and output of files is <fstream>.

You must declare any file streams before you use them to read and write data. For example, the following statements inform the compiler to create a stream called in_stream that is an input-file-stream object, <ifstream>, and another called out_stream that is an output-file-stream object, <ofstream>.

ifstream in_stream;

ofstream out_stream;

6.2. Member Functions and Precision¶

A function that is associated with a certain type of object is called a member function of that object. You have already used member functions setf(...) and precision(...) for formatting our output streams using cout. These functions are included briefly below:

// Use cout's member function "set flags", called setf

// The argument here means to use a fixed point rather than scientific notation

cout.setf(ios::fixed);

// Use cout's setf function again, but this time

// The argument tells cout to show the decimal point

cout.setf(ios::showpoint);

// Use cout's member function, called Precision

// The argument indicated to display 2 digits of precision

cout.precision(2);

6.3. File Operations¶

Having created a stream with the declaration above, we can connect it to a file (i.e. open the file) using the member function open(filename). For example, the following statement will allow the C++ program to open the file called “myFile.txt”, assuming a file named that exists in the current directory, and connect in_stream to the beginning of the file:

in_stream.open("myFile.txt");

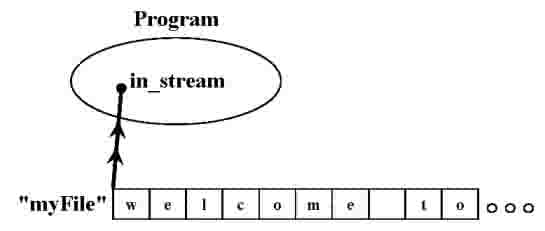

Once connected, the program can read from that file. Pictorially, this is what happens:

the <ofstream> class also has an open(filename) member function, but it is defined differently. Consider the following statement:

out_stream.open("anotherFile.txt");

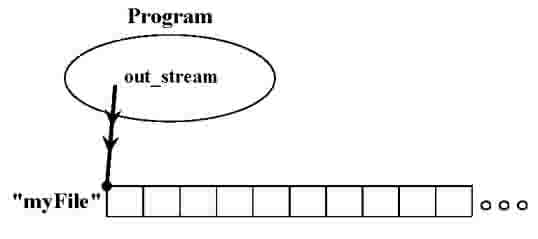

Pictorally, we get a stream of data flowing out of the program:

Because out_stream is an object of type <ofstream>, connecting it to the file named “anotherFile.txt” will create that file if it does not exist. If the file “anotherFile.txt” already exists, it will be wiped and replaced with whatever is fed into the output stream.

To disconnect the ifstream in_stream from whatever file it opened, we use its close() member function:

in_stream.close();

To close the file for out_stream, we use its close() function, which also adds an end-of-file marker to indicate where the end of the file is:

out_stream.close();

Answer the question below concerning the use of the fstream library:

- Yes, ofstream is required to edit the file.

- Wrong! Even though it is required for editing files, using ofstream first will cause problems when it opens a file that has previous work saved on it.

- Yes, using ifstream will wipe the file clean without using ofstream first.

- Wrong! ifstream is only used to read files, therefore it will never edit the contents of one.

- No, using ofstream on a file that already has information on it will clear the entire file.

- Correct!

- No, ofstream is exclusively used for reading files.

- Wrong! ifstream is used to read files instead.

Q-1: Say you wanted to add some text to a file that already has important information on it.

Would it be a good idea to first use ofstream to open the file?

6.4. Dealing with I/O Failures¶

File operations, such as opening and closing files, are often a source of runtime

errors for various reasons. Well-written programs always should include error checking

and Handling routines for possible problems dealing with files. Error checking

and handling generally involves the programmer inserting statements in functions

that perform I/O to check if any of the operations have failed. In C (the predecessor to C++),

the system call to open a file returns a value after the function is called.

A negative number means the operation failed for some reason, which the program can

check to see if reading from a file is alright. In C++, a simple error checking mechanism

is provided by the member function fail():

in_stream.fail();

This function returns true only if the previous stream operation for in_stream

was not successful, such as if we tried to open a non-existent file. If a failure has

occured, in_stream may be in a corrupted state and it is best not to attempt any more

operations with it.

The following example code fragment safely quits the program entirely in case an I/O operation fails:

After opening the “myFile.txt” file, the if conditional checks to see if there was an error. If so, the program will output the apologetic error message and then exit. The exit(1) function from the library cstdlib enables the program to terminate at that point and have it return a “1” versus a “0”, indicating an Error has occurred.

For more on Error Handling, see section 1.11.

6.5. Reading and Writing with File Streams¶

As file I/O streams work in a similar way to cin and cout, the operators “>>” and “<<” perform the same direction of data for files, with the exact same syntax.

For example, execution of the following statement will write the number 25, a line break, the number 15, and another line break into the out_stream output stream.

out_stream << 25 << endl;

out_stream << 15 << endl;

The line break after the value 25 is important because data in a text file is typically seperated by a space, tab, or a line break. Without the line break, the value 2515 will be placed in the file, and subsequent read operations on that file would consider 2515 as a single value. For example, suppose that after the previous statement, the program opens the same file with the input stream in_stream. The following statement would put the number 25 into the variable inputn.

int inputn;

in_stream >> inputn;

6.6. The End-Of-File (EOF) for Systems that Implement eof()¶

So far, the assumption was that the programmer knew exactly how much data to read from an open file. However, it is common for a program to keep reading from a file without any idea how much data exists. Most versions of C++ incorporate an end-of-file (EOF) flag at the end of the file to let programs know when to stop. Otherwise, they could read data from a different file that happened to be right after it in the hard drive, which can be disastrous.

Many development environments have I/O libraries that define how the member

function eof() works for ifstream variables to test if this flag is set to true or false. Typically, one would like to know when the EOF has not been reached, so a common way is a negative boolean value. An alternative implementation is to keep reading using the >> operator; if that operation was successful (i.e. there was something in the file that was read), this success is interpreted as a 1 (true).

Incidentally, that is why if you forget the second equals sign in a comparison

between a variable and a value, you are assigning the value to the variable,

which is a successful operation, which means the condition ends up evaluating to true.

The following two code fragments highlight the possibilities:

Using the eof() member function

while(!in_stream.eof()) {

// statements to execute

// while EOF has not been

// reached

}

Using the >> operator

while(in_stream>>inputn) {

// statements to execute

// while reads are successful

}

Here is an example of a program that essentially uses the second technique

mentioned above to read all the numbers in a file and output them in a neater format.

The while loop to scan through a file is located in the make_neat(...) function.

// Illustrates output formatting instructions.

// Read all the numbers in the file rawdata.dat and write the numbers

// to the screen and to the file neat.dat in a neatly formatted way.

#include <cstdlib> // for the exit function

#include <fstream> // for I/O member functions

#include <iomanip> // for the setw function

#include <iostream> // for cout

using namespace std;

void make_neat(

ifstream &messy_file,

ofstream &neat_file,

int number_after_decimalpoint,

int field_width);

int main() {

ifstream fin;

ofstream fout;

fin.open("rawdata.txt");

if (fin.fail()) { // oops the file did not exist for reading?

cout << "Input file opening failed." << endl;

exit(1);

}

fout.open("neat.txt");

if (fout.fail()) { // oops the output file open failed!

cout << "Output file opening failed.\n";

exit(1);

}

make_neat(fin, fout, 5, 12);

fin.close();

fout.close();

cout << "End of program." << endl;

return 0;

}

// Uses iostreams, streams to the screen, and iomanip:

void make_neat(

ifstream &messy_file,

ofstream &neat_file,

int number_after_decimalpoint,

int field_width) {

// set the format for the neater output file.

neat_file.setf(ios::fixed);

neat_file.setf(ios::showpoint);

neat_file.setf(ios::showpos);

neat_file.precision(number_after_decimalpoint);

// set the format for the output to the screen too.

cout.setf(ios::fixed);

cout.setf(ios::showpoint);

cout.setf(ios::showpos);

cout.precision(number_after_decimalpoint);

double next;

while (messy_file >> next) { // while there is still stuff to read

cout << setw(field_width) << next << endl;

neat_file << setw(field_width) << next << endl;

}

}

// Code by Jan Pearce

This is the rawdata.txt inputed into the make_neat(...).

10 -20 30 -40

500 300 -100 1000

-20 2 1 2

10 -20 30 -40

And this is the expected output

+10.00000

-20.00000

+30.00000

-40.00000

+500.00000

+300.00000

-100.00000

+1000.00000

-20.00000

+2.00000

+1.00000

+2.00000

+10.00000

-20.00000

+30.00000

-40.00000

The input file rawdata.txt must be in the same directory (folder) as the program in order for it to open successfully. The program will create a file called “neat.dat” to output the results.

- To keep a program from writing into other files.

- Yes, EOFs are intended to prevent the program from overwriting a file.

- To keep a program from stopping.

- Not quite, the point of EOFs is to do the opposite.

- To make sure you do not overflow into temporary buffer.

- Yes, EOFs prevent overflow into temporary buffer.

- To stop an input files stream.

- Yes, EOFs stop input file streams.

Q-2: What are good use cases for EOFs in C++ programming?

6.7. Passing Streams as Parameters¶

In the above program, you see that the input and output streams are passed to the file

via pass by reference. This fact may at first seem like a surprising choice

until you realize that a stream must be changed in order to read from it or write to it.

In other words, as streams “flow”, they are changed.

For this reason, all streams will always be passed by reference.

6.8. File Names and C-Strings¶

In modern versions of C++, you can use the <string> library for filenames,

but earlier versions of C++ required the use of C-strings.

The program above will try to open the file called “rawdata.txt” and

output its results to a file called “neat.dat” every time it runs,

which is not very flexible. Ideally, the user should be able to enter

filenames that the program will use instead of the same names.

We have previously talked about the char data type that allows users to store

and manipulate a single character at a time. A sequence of characters such as “myFileName.dat”

can be stored in an array of chars called a c-string, which can be declared as follows:

// Syntax: char C-string_name[LEN];

// Example:

char filename[16];

This declaration creates a variable called filename that can hold a string of

length up to 16-1 characters.

The square brackets after the variable name indicate to the compiler the maximum

number of character storage that is needed for the variable.

A \0 or NULL character terminates the C-string, without the system knowing how much of

the array is actually used.

- Warnings:

The number of characters for a c-string must be one greater than the number of actual characters!

Also, LEN must be an integer number or a declared const int, it cannot be a variable.

C-strings are an older type of string that was inherited from the C language, and people frequently refer to both types as “strings”, which can be confusing.

Typically, string from the <string> library should be used in all other cases when not

working with file names or when a modern version of C++ can be used.

6.9. Putting it all Together¶

The following program combines all of the elements above and asks the user for the input and output filenames. After testing for open failures, it will read three numbers from the input file and write the sum into the output file.

#include <cstdlib> // for the exit function

#include <fstream> // for I/O member functions

#include <iostream> // for cout

using namespace std; // To avoid writing std:: before standard library components

int main() {

// Declare variables for file names and file streams

char in_file_name[16], // Arrays to store filenames (max 15 chars + null terminator)

out_file_name[16];

ifstream in_stream; // Input file stream object

ofstream out_stream; // Output file stream object

// Prompt the user for input and output file names

cout << "This program will sum three numbers taken from an input\n"

<< "file and write the sum to an output file." << endl;

cout << "Enter the input file name (maximum of 15 characters):\n";

cin >> in_file_name;

cout << "\nEnter the output file name (maximum of 15 characters):\n";

cin >> out_file_name;

cout << endl;

// Condensed input and output file opening and checking.

in_stream.open(in_file_name);

out_stream.open(out_file_name);

if (in_stream.fail() || out_stream.fail()) {

cout << "Input or output file opening failed.\n";

exit(1); // Terminate the program with an error code

}

// Declare variables to store numbers and their sum

double firstn, secondn, thirdn, sum = 0.0;

// Read the first three numbers from the input file

cout << "Reading numbers from the file " << in_file_name << endl;

in_stream >> firstn >> secondn >> thirdn;

// Calculate the sum of the numbers

sum = firstn + secondn + thirdn;

// The following set of lines will write to the screen

cout << "The sum of the first 3 numbers from " << in_file_name << " is "

<< sum << endl;

cout << "Placing the sum into the file " << out_file_name << endl;

// The following set of lines will write to the output file

out_stream << "The sum of the first 3 numbers from " << in_file_name

<< " is " << sum << endl;

// Close the file streams

in_stream.close();

out_stream.close();

cout << "End of Program." << endl;

return 0;

}

6.10. Summary¶

File handling in C++ uses

streamsimilar to cout and cin in<iosteam>library but is<fstream>for file stream.ifstream in_streamcreates an input stream object, in_stream, that can be used to input text from a file to C++.ofstream out_streamcreates an output stream object,out_steam, that can be used to write text from C++ to a file.End-of-File or

.eof()is a method for the instance variables of fstream, input and output stream objects, and can be used to carry out a task until a file has ended or do some task after a file has ended.

6.11. Check Yourself¶

- fstream

- Yes, fstream is library for handling file input and output.

- ifstream

- No, ifstream is an object type for handling input.

- ofstream

- No, ofstream is an object type for handling output.

- iostream

- Yes, iostream is a library for handling console input and output.

Q-3: Which of the following are libraries for C++ input and output? (Choose all that are true.)

-

Q-4: Drag the corresponding library to what you would use it for.

Which library is used for which task?

- fstream

- I want to write to a file

- iostream

- I want to write to the console