Remark 7.2.1.

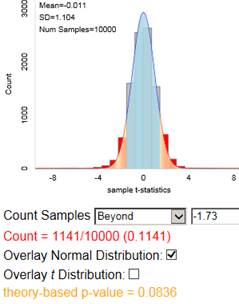

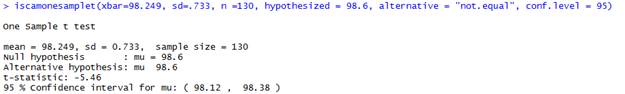

In the previous investigation, we assumed random sampling from a finite population to predict the distribution of sample means and help us evaluate whether a particular value is an unlikely value for the sample mean by chance alone. However, this method is not realistic in practice as we had to make up a population to sample from and we had to make some assumptions about that population (e.g., shape). Luckily, the Central Limit Theorem also predicts how that distribution would behave for most population shapes. But the CLT does require us to know certain characteristics about the population.