Section 6.2 Investigation 2.2: Honking Reaction Times

The study was conducted at a busy intersection in Munich, West Germany, on two afternoons (Sunday and Monday) in 1986.The experimenters sat in a Volkswagen Jetta (the "blocking car") and did not accelerate after the traffic light turned green, and timed how long before the driver of the blocked car reacted (either by honking or flashing headlights). The response time (in seconds) is our variable of interest. Some values were "censored" in that the researcher stopped timing before the driver actually honked. This can happen if there is a time limit to the observation period and "success" has not been observed within that time period.

The data for the above study can be found in honking.txt.

Checkpoint 6.2.1. Predict your reaction time.

Checkpoint 6.2.2. Explore honking reaction time data.

-

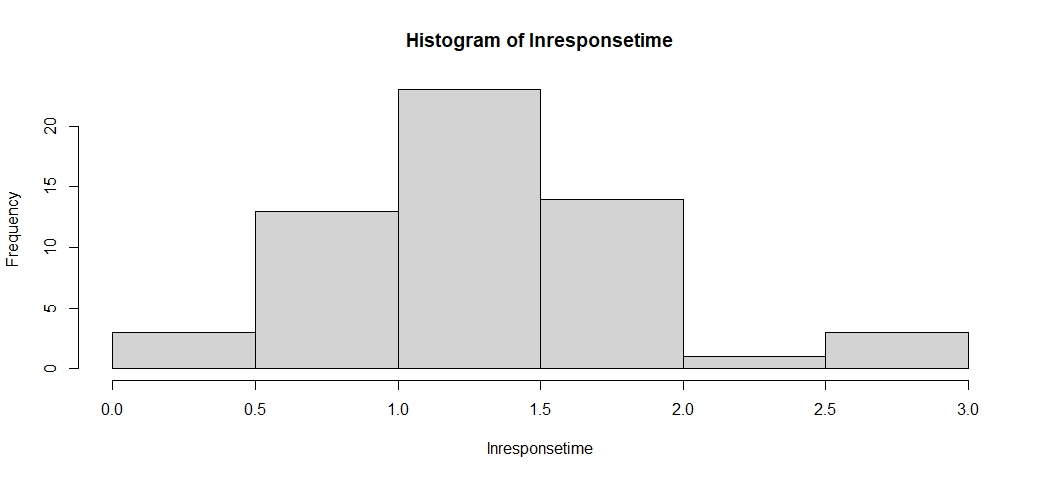

Use technology to create a histogram and describe the behavior of the data – shape, center, spread, outliers (suggest an explanation?).

-

Then overlay a normal probability model. Do these data behave like a normal distribution? If not, how do they deviate from normality? Does the shape make sense in this context?

-

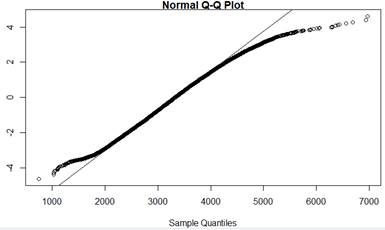

Also examine a normal probability plot and discuss how deviations from the line correspond to the nonnormal shape you are observing.

Solution.

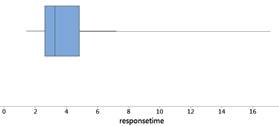

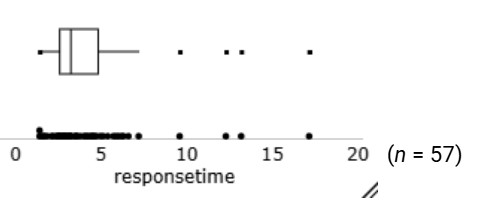

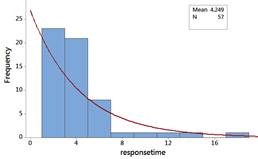

The distribution of response times are skewed to the right. Most people waited less than 5 seconds, but a couple waited more than 15 seconds. There is one outlier 17.15 seconds.

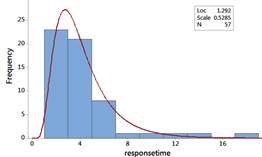

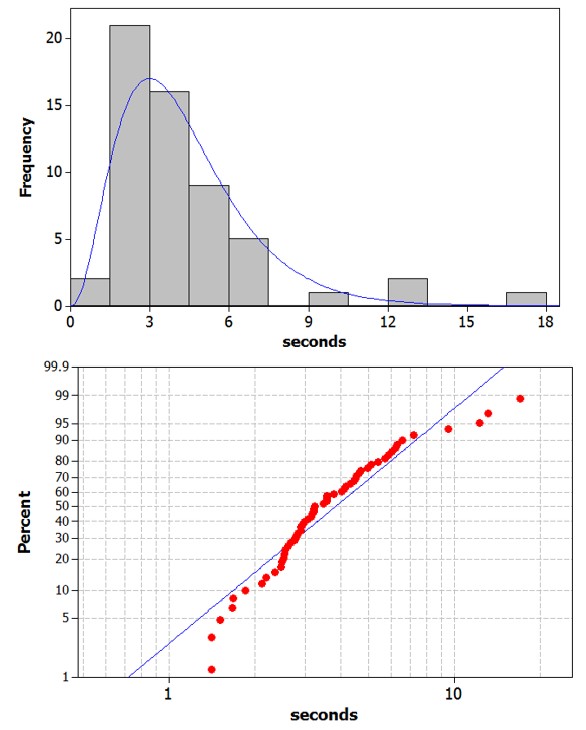

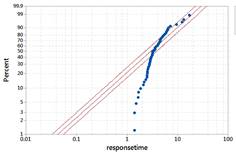

Example output:

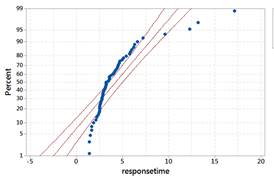

The data do not behave like a normal distribution. The probability plot confirms that the largest response times are larger than we would expect from a normal distribution and the lowest response times are larger than we would expect.

Checkpoint 6.2.3. Compare mean and median.

Hint.

Definition: Resistant Statistic.

A numerical summary (statistic) is said to be resistant when it is not strongly influenced by a change in one or two extreme data values.

When data are skewed to the right/left, the mean will be pulled in the direction of the longer tail.

When data are skewed, we might often prefer to report the median as a "typical" value in the data set, rather than the mean because the mean is pulled in the direction of the longer tail. In addition, you might not want to cite the standard deviation as a measure of spread in a skewed distribution.

Definition: Interquartile Range (IQR).

Interquartile range (IQR) = upper quartile – lower quartile

The lower quartile is a value such that roughly one-fourth of all the observations fall below it; the upper quartile is a value such that roughly one-fourth of all the observations fall above it. The IQR then measures the width of the interval containing the middle 50% of the observations.

Checkpoint 6.2.4. Compute interquartile range.

Hint.

Checkpoint 6.2.5. IQR as resistant measure.

Would you consider the IQR a resistant measure of spread?

- Yes

- No

When the data are skewed, the median and interquartile range are often considered better numerical summaries of the center and variability of the distribution than the mean and standard deviation. When working with the median and interquartile range, we often report the five number summary which consists of the minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile, and maximum values.

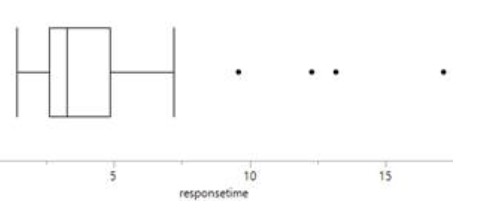

Definition: Boxplot.

Another graph is based on the five-number summary, called a boxplot (invented by John Tukey in 1970). The box extends from the lower quartile to the upper quartile with a vertical line inside the box at the location of the median. Whiskers then typically extend to the min and max values.

Checkpoint 6.2.6. Create boxplot by hand.

Create by hand a boxplot for these data. Which display do you prefer, the boxplot or the histogram? Why?

Although boxplots are a nice visual of the five-number summary, they can sometimes miss interesting features in a data set. In particular, shape can be more difficult to judge in a boxplot, and they usually don’t provide information about the size of a data set.

Another application of the inter-quartile range is as a way to measure how far an observation is from the bulk of the distribution.

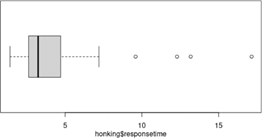

Definition: Outlier Criterion and Modified Boxplot.

A value is an outlier according to the 1.5IQR criterion if the value is larger than the upper quartile + 1.5 × box length or smaller than the lower quartile – 1.5 × box length.

Note: The box length = upper quartile – lower quartile, is the interquartile range.

A modified boxplot will display such outliers separately and then extend the whiskers to the most extreme non-outlier observation.

Technology Detour – Modified Boxplots.

Use the following Technology Detour to create a "modified" boxplot for these data.

Checkpoint 6.2.7. Modified Boxplot in Descriptive Statistics Applet.

Use the Descriptive Statistics applet.

Checkpoint 6.2.8. Modified Boxplot in R.

boxplot(responsetime, ylab="time until reaction", # Adds labels

horizontal=TRUE) # Makes horizontal

# OR

iscamboxplot(responsetime, xlab="time until reaction") # Uses quartiles

Checkpoint 6.2.9. Modified Boxplot in JMP.

In the Distributions window, use the hot spot to select Outlier Boxplot.

Checkpoint 6.2.10. Counting outliers.

Are there any outliers according to these criteria?

These data are not well modelled by a normal distribution. So can we still make predictions? There are a couple of strategies. One would be to consider whether a rescaling or transformation of the data might create a more normal-looking distribution, allowing us to use the methods from Investigation 2.1. In this case, we need a transformation that will downsize the large values more than the small values. Log transformations are often very helpful in this regard.

Definition: Data Transformation.

A data transformation applies a mathematical function to each value to re-express the data on an alternative scale. Data transformations can also make the data more closely modeled with a normal distribution, which could then satisfy the conditions the Central Limit Theorem.

Checkpoint 6.2.11. Log transformation.

Create a new variable which is log(responsetime). (You can use either natural log or log base 10, but so we all do the same thing, let’s use natural log here, which is the default in most software when you say "log.")

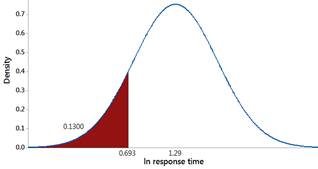

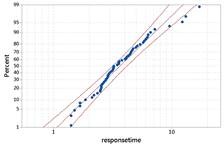

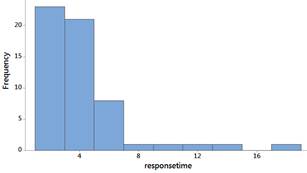

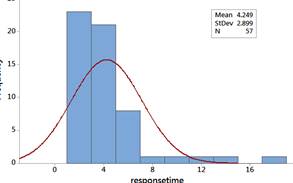

Create a histogram of these data and a normal probability plot. Does log(responsetime) approximately follow a normal distribution? What are the mean and standard deviation of this distribution?

Hint 2. In JMP

Checkpoint 6.2.12. Predict using normal distribution on log scale.

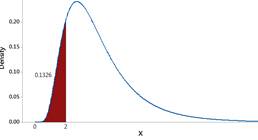

Use a normal distribution with mean 1.29 ln-sec and standard deviation 0.53 ln-seconds for the logged response times and predict how often someone will honk within the first 2 seconds.

Checkpoint 6.2.13. Compare prediction to observed data.

How does this prediction in Checkpoint 6.2.12 compare to the observed percentage honking within the first 2 seconds in the data set?

Alternative Probability Models.

Another approach is to fit a different mathematical model to the original data:

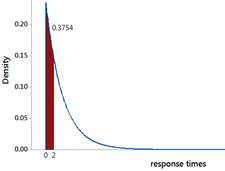

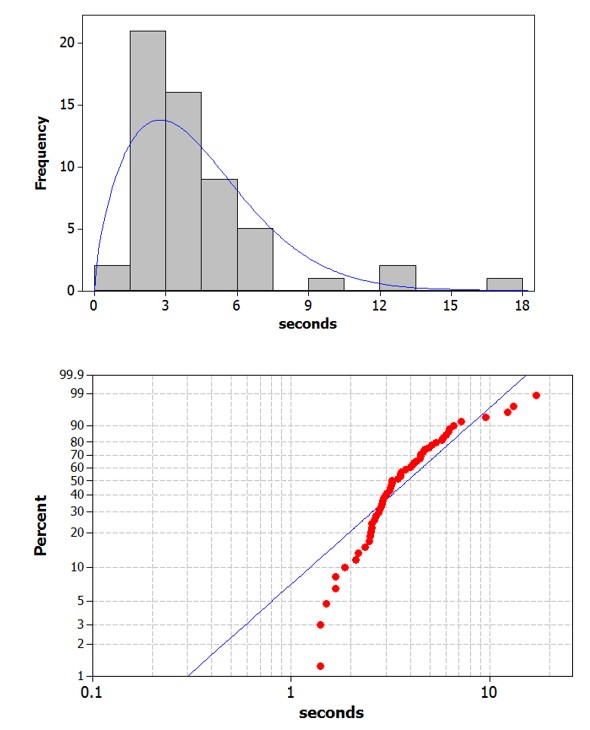

Checkpoint 6.2.14. Exponential probability model.

Use technology to overlay an exponential probability model (often used to model wait times) to these data and/or create a probability plot using the exponential distribution as the reference distribution.

Describe the behavior of the exponential distribution. Does it appear to be a reasonable fit for these data? Describe any deviations.

Hint 1. In R

For the qqplot we have to first get the quantiles:

theoquant = qexp(ppoints(12)) # Generates 1/n quantiles for 12 observations

# from exponential distribution

hist(theoquant)

qqplot(responsetime, theoquant) # Your data vs. quantiles. Look for a line.

iscamaddexp(responsetime) # overlay exponential model

Hint 2. In JMP

Solution.

The exponential is skewed to the right with its peak at zero. This does not appear to be as good of a fit. We have more observations around 4-5 seconds than the exponential distribution would predict and fewer observations less than 1 second (we don’t have any, the times could be rounded in the dataset?).

Checkpoint 6.2.15. Calculate probability using exponential distribution.

Use technology to calculate the probability of a wait time under 2 seconds using the exponential distribution with mean 4.25 sec

Hint 2. In JMP

Checkpoint 6.2.16. Lognormal distribution.

Note: This is equivalent to fitting the normal distribution on the log-transformed data!

Hint 1. In R

qqplot(responsetime, qlnorm(ppoints(12)))

iscamaddlnorm(responsetime)

plnorm(2, meanlog = 1.292, sdlog = 0.5238)

Hint 2. In JMP

Discussion.

There are of course, many other probability models we could look into. One limitation of the exponential distribution is that it assumes the same value for the mean and the standard deviation, clearly not the case for these data. There are other more flexible distributions (e.g., Gamma and Weibull) that use two parameters to characterize the distribution rather than only one.

Checkpoint 6.2.17. Generalization of results.

To what population are you willing to generalize these results? Explain.

Hint.

Checkpoint 6.2.18. Future research directions.

If you were to continue to explore this research area/data set, what would you be interested in investigating next?

Study Conclusions.

In this study, we found that the amount of time a blocked driver waits before responding follows a skewed right distribution with a mean of 4.25 seconds and a median of 3.24 seconds, with a few drivers waiting more than 10 seconds. Although the dataset is small, we might consider using these data to build a mathematical model for these skewed data, either using a transformation or a probability model other than the normal distribution, to help predict future results (e.g., a wait time of less than 2 seconds). These researchers were actually interested in whether the "social status" of the blocked car was related to how long it took before people honked. They found that "the mean and median response times decreased monotonically with the status of car, except when the blocked car was very small." Similar results had been found in an earlier study by Doob and Gross in the United States (1968) which varied the status of the blocking car. However, neither study was replicated by a Swiss study (Jann, Suhner, & Marioni, 1995), perhaps due to cultural differences.

Subsection 6.2.1 Practice Problem 2.2A

A group of Cal Poly students (Sasscer, Mease, Tanenbaum, and Hansen, 2009) conducted the following study: volunteers were to say "go," and then to say "stop" when they believed 30 seconds had passed. The researchers asked the participants to not count in their heads and recorded how much time had actually passed. The data are in 30seconds.txt.

Checkpoint 6.2.19. Examine distribution of 30-second estimates.

Examine graphical and numerical summaries of these data. Describe the shape of the distribution. How do the mean and median compare? Is the skewness statistic positive or negative? What does this tell you about whether people tend to over or underestimate the length of 30 seconds?

Checkpoint 6.2.20. Assess normal model appropriateness.

Does a normal model seem appropriate here?

Checkpoint 6.2.21. Evaluate log transformation.

Does a log transformation succeed in creating a normal distribution? Explain how you might have predicted this answer based on the first graph you looked at in part (a).

Checkpoint 6.2.22. Generalization of results.

To what population would you be willing to generalize these data?

Subsection 6.2.2 Practice Problem 2.2B

Checkpoint 6.2.23. Compare Weibull and Gamma fits.

You have attempted of activities on this page.