Loading from URL (In RStudio)

If you’re using RStudio on your computer, you can load the

InfantData.txt file directly from the web using the

url() function:

InfantData = read.table(url("https://www.rossmanchance.com/iscam3/data/InfantData.txt"), header=TRUE)

The

header=TRUE argument indicates the first row contains variable names.

Loading from Your Computer

If you’ve downloaded the

InfantData.txt file, use

file.choose() to browse for it:

InfantData = read.table(file.choose(), header=TRUE)

For This Interactive Textbook (Sage Cell)

Since the Sage cells in this textbook cannot access external URLs, we’ll create the data directly. Click “Evaluate (R)” below to load and view the Infant data:

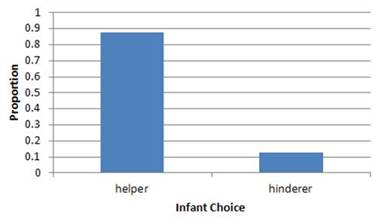

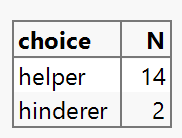

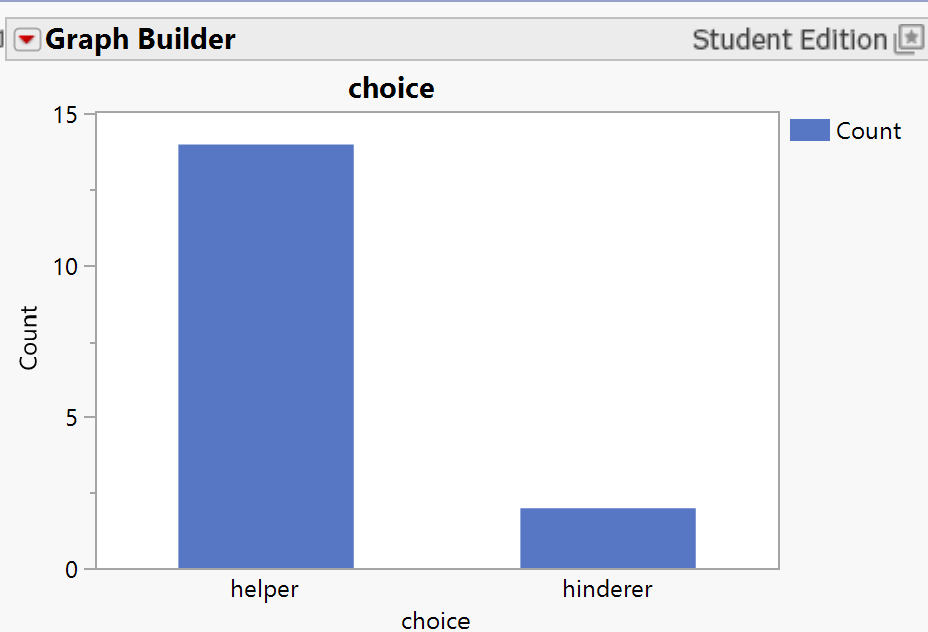

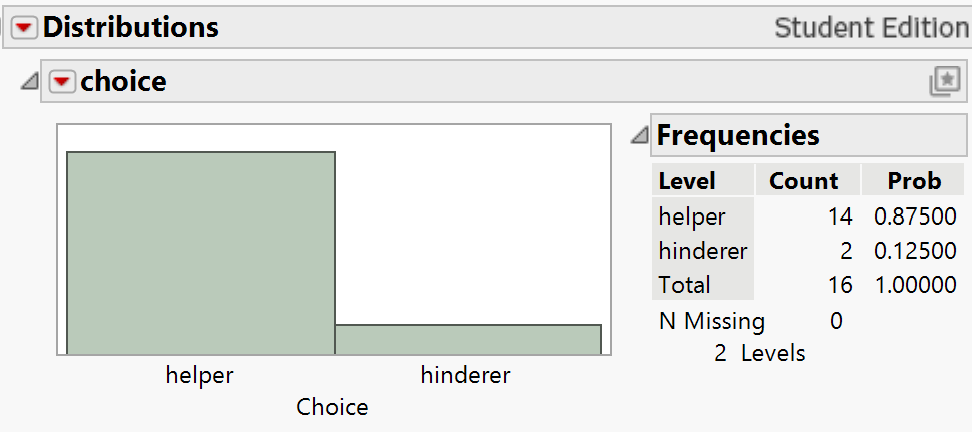

You should see output showing the data with 16 rows and one column called

choice. Verify that you see both "Helper" and "Hinderer" values.

Or you need to clarify to R which datafile you are using (e.g.,

InfantData$choice).

Depending on how the data you are pasting is formatted, you may need additional arguments:

-

sep="\t" - separated by tabs

-

na.strings="*" - how to code missing values

-

strip.white=TRUE - strip extra white space

Solution.

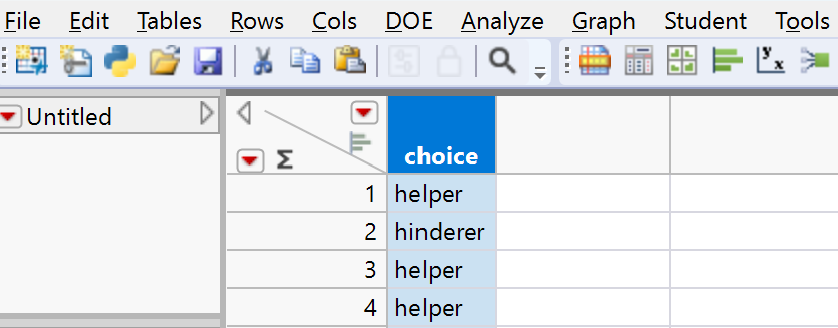

After running

head(InfantData), you should see output similar to:

choice

1 Helper

2 Helper

3 Helper

4 Helper

5 Helper

6 Hinderer

This shows the first 6 observations of the data. The full dataset contains 16 observations total.